50 Shades of Richter

BY: -

It is with a certain heaviness of spirit that I write this introduction, aware that what I am about to reveal could not only create me enmities in the artistic and academic community but also become a veritable scarlet letter, indelibly marking my career. Yet, I feel the duty to share with the reader, and even more so with myself, what might be the most outrageous secret of the art world in the last century.

The entire history of art is punctuated with thefts and robberies: lost and found works, others lost forever, destroyed or hidden away in some attic and forgotten. However, in today's society, where everything seems to be under the watchful and constant eye of digital surveillance, it becomes increasingly difficult to imagine that priceless art masterpieces can be stolen with impunity. Yet, examples like America, the toilet created by Maurizio Cattelan, stolen in 2019 from Blenheim Palace in England, demonstrate how the reality around us is less predictable than one might expect. If this example is not enough to convince the reader, just look at the past twenty-five years to add to the list of disappeared works: a Cézanne in 1999, a Van Gogh in 2002, a Monet seascape vanished in 2006 along with other works by Dalí, Picasso, and Matisse, and a Frans Van Miers stolen in broad daylight from the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney in 2007.

In short, works of artists who have now entered the pantheon of art history have disappeared despite the sophisticated surveillance systems of the museums that housed them. Now I ask the reader how many of these thefts were actually aware of. Well, if even only a fraction of these were unknown to them, what can be the awareness about a disappeared work that no media has reported? Just like for mine before stumbling upon the clues that I will shortly expose: none.

Before revealing my thesis and perhaps the deception, a brief digression into art theory is necessary. Brief because the topic has already been extensively covered by other authors before me, but necessary as it is an essential part of this investigation. Everyone knows that the work of art has transcended its pure objectivity for over a century. Already with Walter Benjamin and his analysis of technical reproducibility in art, a breach had been opened in the concept of uniqueness and authenticity of the work. Today, even the most naive art enthusiast knows that from a semiotic perspective, the work transcends its nature as a pure signifier in favor of signified. Therefore, Duchamp's original urinal, disappeared after its first exhibition, even though now reproduced, retains the same artistic power as then. And to cite a more recent case, the original shark from Damien Hirst's The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living was replaced with a second one when the first began to deteriorate. In this case too, the objectual nature of the work has changed, but not the artistic one. As anticipated, none of this will be particularly original for the reader, but it is essential to keep it in mind when reading what follows.

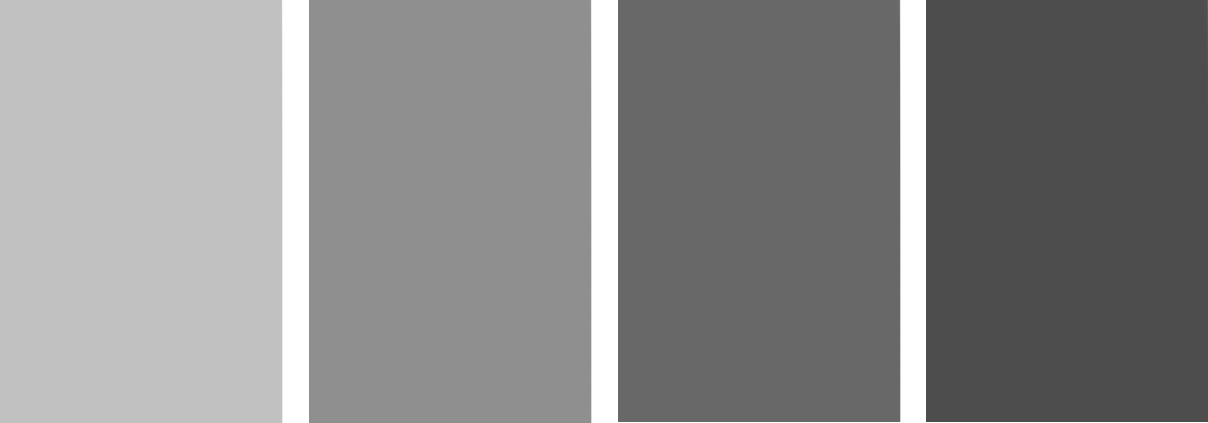

Last year, I was engaged in preparing material for a research project on museum management in the post-Covid19 period. During this time, I found myself in a well-known contemporary art museum. During this visit, after almost forty years, I had the pleasure of seeing one of Gerhard Richter's works from the Grey series. The work, as the title suggests, is part of a corpus of works in which the German artist explored the gray surface as a form of indifference. A way to cleanse the pictorial surface of any ideology. I still remember the day I saw another painting from the same series for the first time; at that moment, immersed in the ideological radicalism of the Cold War, the indifference of that gray had the power of a scream in the art world. Well, last year, in front of the same work, I felt nothing. Absolutely nothing. You can imagine my surprise. A couple of days later, I returned to visit the museum and spent a good amount of time in front of the work. Again, I did not feel that iconoclastic and anti-ideological power. Something had changed. One thing I noticed, however, was the discomfort, if not outright suspicion, with which the museum staff began to look at me after I had spent a long time in front of the work. Aware of the tension among the personnel, I decided to get to the bottom of the matter. I asked one of them if it was possible to speak with the director, but I was told that he was out of town and would not be available for a few days. Just the time would take me to pack up and leave, I thought to myself.

I returned home with a vague unease in my soul, but as the days passed and I became absorbed in my work, this feeling slowly settled at the back of my mind. Weeks and months went by until one winter afternoon when I accidentally stumbled upon an old photo of the Grey in my archive, a piece I had seen and photographed years before at a German gallery. Carefully examining the old black-and-white photo, the slightly yellowed paper and the small printing defects on the surface transported me back to those years. To my great surprise, the gray surface of the canvas struck me almost as forcefully as it had back then. It was still just a photo, I told myself; I couldn't expect the same effect. However, what was strange was that, unlike the work in the museum I had visited shortly before, this one still held power over me. Its meaning had not dissolved.

I decided to delve deeper, realizing that the only solution was to find the painting and admire it in person. I discovered that it was part of the collection of a famous European museum and hurried to pay it a visit. The journey to the museum was simple, but what proved more complex was my interaction with the museum director after observing the painting. Again, not feeling any connection to the artwork, I expressed my perplexities about the work to them. Had the painting remained the same? Was it the signifier or the signified that had changed? Could we still consider the work authentic if its meaning was lost in the context of our post-ideological contemporaneity? Or perhaps... what if the original painting had been replaced with a new one, exactly identical but lacking the original and meaningful power? Was I crazy to question it, or was I simply facing another intricately woven deception by the highest spheres of the art system?

Without much surprise, I was accused of charlatanism and pointed at as a liar and a braggart. As the reader is well aware of the vast sums of money revolving around Richter's works, it's not unexpected that my hypothesis was dismissed as a delusion. The economic impact of my supposition, if confirmed, would be catastrophic.

At this point, all that remains is to sum up this whole affair, knowing that by doing so, I will make enemies of important museum institutions and wealthy collectors alike. But can we consider authentic a work that has lost its communicative power? Can a work that has not changed but has lost the power behind its message due to a change in the political context still be the same? I leave this answer to the philosophers, but what if there is another secret to unveil, that should be kept untold. What if not only the two Grey paintings I saw but all the grey shades of Richter were secretly replaced by identical copies, yet devoid of their original communicative power? I cannot provide an answers or proofs to this question, aside from my personal feelings, but, to quote the Italian politician Giulio Andreotti, "Thinking badly of others is a sin, but often it's right."

The entire history of art is punctuated with thefts and robberies: lost and found works, others lost forever, destroyed or hidden away in some attic and forgotten. However, in today's society, where everything seems to be under the watchful and constant eye of digital surveillance, it becomes increasingly difficult to imagine that priceless art masterpieces can be stolen with impunity. Yet, examples like America, the toilet created by Maurizio Cattelan, stolen in 2019 from Blenheim Palace in England, demonstrate how the reality around us is less predictable than one might expect. If this example is not enough to convince the reader, just look at the past twenty-five years to add to the list of disappeared works: a Cézanne in 1999, a Van Gogh in 2002, a Monet seascape vanished in 2006 along with other works by Dalí, Picasso, and Matisse, and a Frans Van Miers stolen in broad daylight from the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney in 2007.

In short, works of artists who have now entered the pantheon of art history have disappeared despite the sophisticated surveillance systems of the museums that housed them. Now I ask the reader how many of these thefts were actually aware of. Well, if even only a fraction of these were unknown to them, what can be the awareness about a disappeared work that no media has reported? Just like for mine before stumbling upon the clues that I will shortly expose: none.

Before revealing my thesis and perhaps the deception, a brief digression into art theory is necessary. Brief because the topic has already been extensively covered by other authors before me, but necessary as it is an essential part of this investigation. Everyone knows that the work of art has transcended its pure objectivity for over a century. Already with Walter Benjamin and his analysis of technical reproducibility in art, a breach had been opened in the concept of uniqueness and authenticity of the work. Today, even the most naive art enthusiast knows that from a semiotic perspective, the work transcends its nature as a pure signifier in favor of signified. Therefore, Duchamp's original urinal, disappeared after its first exhibition, even though now reproduced, retains the same artistic power as then. And to cite a more recent case, the original shark from Damien Hirst's The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living was replaced with a second one when the first began to deteriorate. In this case too, the objectual nature of the work has changed, but not the artistic one. As anticipated, none of this will be particularly original for the reader, but it is essential to keep it in mind when reading what follows.

Last year, I was engaged in preparing material for a research project on museum management in the post-Covid19 period. During this time, I found myself in a well-known contemporary art museum. During this visit, after almost forty years, I had the pleasure of seeing one of Gerhard Richter's works from the Grey series. The work, as the title suggests, is part of a corpus of works in which the German artist explored the gray surface as a form of indifference. A way to cleanse the pictorial surface of any ideology. I still remember the day I saw another painting from the same series for the first time; at that moment, immersed in the ideological radicalism of the Cold War, the indifference of that gray had the power of a scream in the art world. Well, last year, in front of the same work, I felt nothing. Absolutely nothing. You can imagine my surprise. A couple of days later, I returned to visit the museum and spent a good amount of time in front of the work. Again, I did not feel that iconoclastic and anti-ideological power. Something had changed. One thing I noticed, however, was the discomfort, if not outright suspicion, with which the museum staff began to look at me after I had spent a long time in front of the work. Aware of the tension among the personnel, I decided to get to the bottom of the matter. I asked one of them if it was possible to speak with the director, but I was told that he was out of town and would not be available for a few days. Just the time would take me to pack up and leave, I thought to myself.

I returned home with a vague unease in my soul, but as the days passed and I became absorbed in my work, this feeling slowly settled at the back of my mind. Weeks and months went by until one winter afternoon when I accidentally stumbled upon an old photo of the Grey in my archive, a piece I had seen and photographed years before at a German gallery. Carefully examining the old black-and-white photo, the slightly yellowed paper and the small printing defects on the surface transported me back to those years. To my great surprise, the gray surface of the canvas struck me almost as forcefully as it had back then. It was still just a photo, I told myself; I couldn't expect the same effect. However, what was strange was that, unlike the work in the museum I had visited shortly before, this one still held power over me. Its meaning had not dissolved.

I decided to delve deeper, realizing that the only solution was to find the painting and admire it in person. I discovered that it was part of the collection of a famous European museum and hurried to pay it a visit. The journey to the museum was simple, but what proved more complex was my interaction with the museum director after observing the painting. Again, not feeling any connection to the artwork, I expressed my perplexities about the work to them. Had the painting remained the same? Was it the signifier or the signified that had changed? Could we still consider the work authentic if its meaning was lost in the context of our post-ideological contemporaneity? Or perhaps... what if the original painting had been replaced with a new one, exactly identical but lacking the original and meaningful power? Was I crazy to question it, or was I simply facing another intricately woven deception by the highest spheres of the art system?

Without much surprise, I was accused of charlatanism and pointed at as a liar and a braggart. As the reader is well aware of the vast sums of money revolving around Richter's works, it's not unexpected that my hypothesis was dismissed as a delusion. The economic impact of my supposition, if confirmed, would be catastrophic.

At this point, all that remains is to sum up this whole affair, knowing that by doing so, I will make enemies of important museum institutions and wealthy collectors alike. But can we consider authentic a work that has lost its communicative power? Can a work that has not changed but has lost the power behind its message due to a change in the political context still be the same? I leave this answer to the philosophers, but what if there is another secret to unveil, that should be kept untold. What if not only the two Grey paintings I saw but all the grey shades of Richter were secretly replaced by identical copies, yet devoid of their original communicative power? I cannot provide an answers or proofs to this question, aside from my personal feelings, but, to quote the Italian politician Giulio Andreotti, "Thinking badly of others is a sin, but often it's right."